I am not ashamed to admit that I absolutely adore the film Event Horizon (1997, dir. Paul W. S. Anderson). The tale of a spaceship – the eponymous Event Horizon – reappearing seven years after going missing during its maiden voyage, now seemingly sentient and intent on tormenting and murdering the rescue party sent to look for survivors (of which, naturally, there are none), combines my two major passions other than medieval history: science fiction and future-horror. Over the course of the film it is determined that the ship’s experimental Gravity Drive, developed by Dr Weir (a dependable as always Sam Neill) did not, in fact, open up an artificial black hole to Proxima Centauri, but sent the crew headlong into a chaotic hell dimension. ‘Libera te tutemet ex inferis’ (save yourself from hell) are the words issued by the Event Horizon’s original captain, recorded on the salvaged flight log, as he holds out his gauged-out eyes towards the camera.

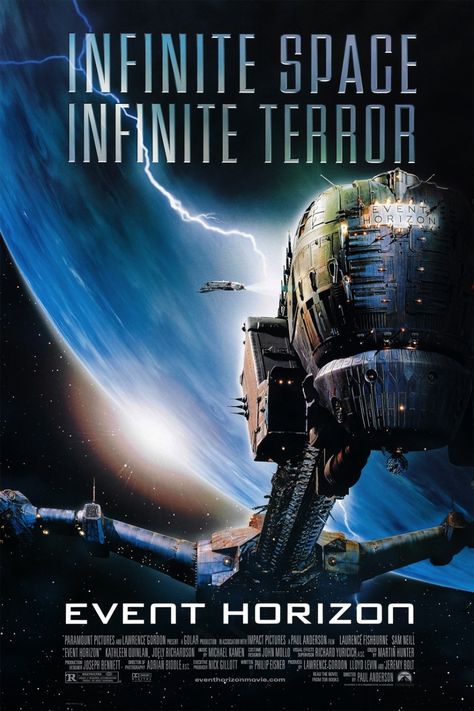

Film poster for Event Horizon, Copyright 1997, © Paramount Pictures

It transpires that the Event Horizon brought a slither of hell back with it. The crew of the aforementioned rescue ship, The Lewis and Clark, led by Captain Miller (an equally dependable Laurence Fishbourne), come to realise that the Event Horizon, now more than just a hulking metal edifice, is able to make manifest their worst traumas and fears. The breakdown of the boundary between the physical and metaphysical worlds, the unbidden manifestation of unreconciled desires and heartache, is a common conceit in horror-infused science fiction, as seen in Stanisław Lem’s Solaris (1972, dir. Andrei Tarkovsky), Michael Crichton’s Sphere (1998, dir. Barry Levinson) and the more recent TV adaptation of George R. R. Martin’s novella, Nightflyers (2018). With its pointedly gothic accruements – Paul W. S. Anderson notes that the design of the spaceship was modelled on Notre Dame Cathedral – the malign agency of the Event Horizon lends itself to be analysed via the lens of medieval demonology. That is to say, if the film’s narrative leads us to believe that the ship did indeed make an unexpected trip to ‘Hell’ on its maiden voyage, can the method of its provocations be explored through equally orthodox terms?

The Event Horizon is able to peer into the minds of the Lewis and Clark crew, tailoring its torments accordingly: Dr Weir is haunted by the manifestation of his suicidal wife; Peters (played by Kathleen Quinlan), the ship’s medieval technician, is taunted by the child she believes she abandoned. ‘It knows my fears, it knows my secrets; gets into your mind and shows you’ says Captain Miller, confronted the burning corpse of a former shipmate he was unable to save. In late medieval theology, demons were believed to possess the ability to torment their victims through the manipulation of their sense apparatus. The Dominican theologian Thomas Aquinas, for example, notes in his De Malo (c.1267–71) that evil spirits were often permitted by God to infiltrate (and manipulate) the internal mechanisms of the human body, subtly altering its humoural makeup in order to cause visions and sensory hallucinations. Of course, the feeling of terror is somewhat perspectival. What may have been horrifying to one person may not have had the same emotional impact on another. How, then, did demons determine the type of hallucinations (or other such sensory effects) to inflict upon their victims? To paraphrase Aquinas’s De Malo, it was through the careful and nuanced observation of human signs, activities and behaviours that demons could arrive at an accurate picture of a person’s psychological makeup. The expert observational skills of demonic entities belong to a tradition that extends back to the authority of Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies (615–30) and Augustine’s De Genesi ad litteram (401-15). Orthodox belief taught that devils were unable to see into a person’s soul. Only God had that right. Despite this, the body (including the mind) gave up other clues that could be easily exploited. There were myriad ways in which an airy demon could deceive and ensnare the unwary.

“Hell is just a word, the reality is much worse”, says the now-possessed Dr Weir during his final confrontation with Captain Miller, just before the aft section of the Event Horizon is pulled into the re-opened black hole, returning once more to the realm of chaos. Although some scholars argue that the film does not actually confirm whether the Event Horizon displays sentience, it is apparent that the manifestation of Weir’s dead wife is the avatar through which the ship tempts and ultimately dooms Dr Weir, who, now spiritually enmeshed with his terrible creation, takes on the antagonist’s role in the film’s climax. If read alongside the works of Augustine, Aquinas et al, the ship displays all the qualities of a seething, contentious demon, especially in the medieval mode. It tests, it torments; it burrows into the anxieties of those it wishes to harm. Some, like Dr Weir, it consumes and takes over. Others, like the unfortunate Technician Peters, it tricks into accidentally killing themselves. Much like the activities of trickster devils recorded in orthodox miracle collections, such as Caesarius of Heisterbach’s Dialogus Miraculorum (c.1220), the ship wants to drag its ‘new crew’ body and soul into Hell. It may be a giant evil spaceship, but the Event Horizon certainly has a medieval way of doing things.

Works Cited:

Thomas Aquinas, The “De Malo” of Thomas Aquinas, ed. by Brian Davies; trans. by Richard Regan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Matt Hills, ‘An Events-Based Definition of Art Horror’, in Dark Thoughts: Philosophic Reflections on Cinematic Horror, ed. by Steven Jay Schneider and Daniel Shaw (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2003), pp. 138–57.

Anna Powell, Deleuze and Horror Film (Ediburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005)